A Journal in Praise of the Art of John Wesley

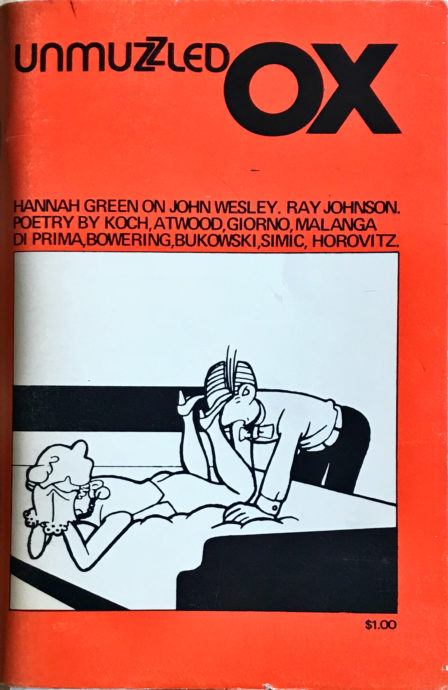

The following text was first published in 1974 in the journal Unmuzzled Ox. It is the first installment of a journal that was continually updated by John Wesley’s late wife, Hannah Green.

December 1973. M is writing about Jack; he is writing a piece on the paintings of John Wesley; he thinks he will call it, ”The Warm Dark Sayings of John Wesley.” He is thinking about Jack; he is studying Jack’s paintings; he is asking Jack questions. They spend all morning at the studio looking at paintings and then we go to lunch at Casey’s and eat snails and drink beer and talk.

M is a poet. A good poet, too. He’s got a wonderfully supple, warm intelligence. He’s quick but gentle, and he’s inquisitive in just the right way. He is setting off for the pure fun of it, it seems, for the intellectual exercise, into a new field—art criticism, art, and the work of John Wesley. He has gone to our heads. Mine as much as Jack’s.

A week has passed. M is looking for an angle. He and Jack spend another afternoon looking at paintings. Then we have dinner at home on Barrow Street. We talk. Heady stuff. I love it all. M is looking for an angle. He thinks it may be the enigmatic quality of the paintings of John Wesley. What is it? Why is it? The enigma.

“Ah,” I say, exhilarated, for now, I see he has arrived at the heart of the secret of Jack’s art, at the heart of its origin.

Jack never does anything obvious. His ideas come as the mind turns (like the globe) into darkness. His mysterious and varied iconography must have a certain magic, a certain mystery for himself as well. Thus his work has the power of true surrealism. Thus his humor is original, unique to John Wesley. Thus the enigma entwined like a riddle in each painting is the result of his psychic method.

Jack never makes the obvious statement it would seem his technique would enable him to do. People ask Jack, “How did you do that?” “Oh, I just traced it,” he says. I’ve heard him say that a hundred times, “Oh, I just traced it.” He starts from a photograph usually. Something catches his eye. It might be the head of Robert E. Lee or U.S. Grant. It might be General Pershing or Pancho Villa. It might be an ad picturing a girl in pantyhose, or a man in waders in the catalog from L.L. Bean, or it might be Donald Duck screaming and tearing out his feathers.

Whatever it is, he traces it, makes a graph, and uses algebra to enlarge it in several stages until the drawing is ready to be transferred onto the canvas. During what would seem, so described, to be a mechanical process, strange and irrational and funny things go on. Accidents are let to happen, the original image is slowly transformed, sometimes repeated and combined with others in moments of wild inspiration. Jack’s wit and sense of humor play on the material; the space of the canvas itself makes certain demands (form); his personal style, his aesthetic sense, his particular sense of elegance, his vision, and his intent shape the forms, work on the images, transforming them, going on until the design is ready to be transferred onto the canvas and brought to life by paint.

In the process, for instance, five Chinese bell boys in a hotel in Hong Kong become a multitude and make the wonderful painting, “Chinese” exhibited in documenta 5 and now owned by Kasper Konig. A little girl who might be the model for Alice in Wonderland has lost her clothes and a dark rabbit with enormous ears has his nose so close to that place between her legs it is almost touching her. That’s the painting, “Sniff.” The head of a man with a large brain and a fine profile in a book by Julian Huxley turns into two men facing each other and one is biting the other’s nose. A single tear falls from the eye of the man who is being bitten. And that’s “Jack Frost.” A frog photographed with its mouth open spitting out something vile tasting becomes three enormous pink frogs with darker pink tongues. Their expressions have become good-natured, lascivious, and happily anticipatory. Over them floats a graceful female nude with her eyes closed; all white she is except for her pink nipples, mouth, fingernails, and toenails matching the dark pink of the frogs’ tongues. The painting is called “Dream of Frogs.”

When Jack began painting seriously in California in the mid-fifties he was about 27, working at Northrop Aircraft as an illustrator. He began as an abstract expressionist. ”A paint slinger,” he says. He learned about composition by being an abstract expressionist. He learned from looking at de Kooning, from looking at Pollock.

“This,” says Jack “is composition: Keep the eye in the painting. Keep the eye in one locked device, limited by edges.” One of the secrets of composition is to keep the lower right-hand corner empty. “Keep the lower right-hand corner empty and the eye will go back into the painting.”

“Keep the lower right-hand corner empty,” Jack says again. If you put the most interesting thing there (in the lower right-hand corner) the eye will leave the· painting as it would the page in reading when it gets to that point.

Jack developed through abstract expressionism into painting hard-edged abstractions, and after he came to New York in 1960 he moved slowly toward painting more and more disciplined stripes.

“Then Jasper Johns opened everything up,” Jack says. “Jasper Johns led the way”. Jack was working in the post office then, and in November 1961, he painted his post office badge in blue and white, a huge badge 72 inches by 72 inches in blue and white, with his own number, 32554, Post Office Department, United States of America, New York, and in the center the swift galloping horse with his tail flying out and his loyal hatted Postman riding close down upon his back. Blue and white stripes with stars in the white stripes extend from the badge’s edges to the edges of the canvas.

Jack painted more badges and emblems and shields in blue and white and grey. Then in the same colors and with tabs as if they were giant emblems, he began painting scenes from the Olympic Games in Los Angeles in 1932. “The last of the innocent Olympic Games,” Jack says. The pictures were in a huge leather-bound book, XX Olympiad, bought by his father who died the following year. Jack painted “Wolfgang Ehrl Congratulates the Champion.” He painted “The Arrival of Count de Baillet-Latour.” He painted the Italian Road Race Team standing behind their bicycles, posing. “Their beautiful boyish faces,” Jack tells me for I have never seen the painting—it is in a private collection in Texas and he has no photograph of it. ”Their beautiful boyish faces,” he says. “So innocent… having come all that way from Italy to Los Angeles to ride their bicycles in that year between the wars. They’d be in their sixties now if they survived the war.”

He painted the head of George Washington with three Indians; he painted Von Hindenberg and Enver Bay; then he pointed to Daniel Boone with his dog.

In November 1962, he painted “Dancing Frogs and Waiting Shark,” now in the collection of Donald Judd where it can occasionally be seen through the windows of Judd’s great old cast-iron building on Spring Street in SoHo. Ten dancing frogs, all white, five in a row, one row on top of the other, the rows tilting just slightly in opposite directions (the frog was taken from a photograph in a biology textbook of a frog being dissected), ten dancing frogs all so gay, dancing on their long, thin frog legs with their little frog hands upraised, so gay and light and all in step; and below them swims a long, grey shark.

The painting is significant, I think, for besides its visual charm and perfection, Jack sounds here for the first time explicitly the deeper theme that runs through his work (and is always there in his mind whether he deals with it directly or not), the theme of mortality: the fleeting, intoxicating joy of life, the ever-presence of death waiting to claim us one by one, Death biding his time like the waiting shark. The theme emerges again explicitly but with a varying note in “Brides” painted in 1965. Four white brides in all, in a row, smile their vacuous smiles, and below is bowed as if in the prayer of a dark man, grey, naked, who represents not death but the knowledge of mortality, the awful awareness of the meaning of desire.

And now, in 1973 and 1974, in luminous form like the memories of childhood, this knowledge of mortality permeates the series, “Searching for Bumstead”—the empty rooms of Bumstead’s house, haunting and lovely, one after another the empty rooms where absence is present and loss is captured.

“It better be funny,” Jack says, trembling with feeling. ”It better be funny,” he says. It better be funny—meaning life, the human predicament.

Jack’s use of repetition is both formal (an answer to the demand of the space of the canvas) and philosophical: repetition makes things funny and it puts things in their proper perspective.

“If you say foot foot foot foot foot foot foot foot foot long enough, then foot becomes hilarious,” Jack says. “If you paint 40 Nixons, it puts Nixon in his place.” He calls it “the Henry Ford Syndrome.”

After seeing Jack’s show a year ago Charlie Pratt said in his marvelous booming voice, “First Jack’s paintings make you laugh. Then you get tears in your eyes.” Romulous Linney said “Jack teaches you a new way to laugh. Then he teaches you a new way to cry.” Archie Miller spoke of some of Jack’s paintings as having a kind of “wacky black humor.” When Jack says something funny, John Brooks looks at him with delight: “You are just like your paintings,” he says.

When Jack first becomes known in New York it was as a Pop Artist. His first show at the Robert Elkon Gallery was in February 1963, and it sold out. April of that year he was included in ”The Popular Image” exhibition in Washington at the Gallery of Modern Art along with Johns, Rauschenberg, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, Rosenquist, Dine, Wesselman, etc. Showing me the catalog that went with the record they made for the show, Jack points to the picture of Johns whom he continues to admire. “Isn’t he beautiful,” Jack says.

Ten years have passed since then and Jack is still associated with the Pop Movement in the public mind, but as time has gone on, it has become clear that he is, rather, an eccentric, absolutely individual, a humorist, a surrealist, “an hermetic visual poet,” as Peter Schjeldahl called him in the Times last year. For me, Jack’s paintings, the best of them, have the lyric quality, the perfection of form, the quality of painting on Greek vases, the quality of certain Oriental painting. It is the quality of line in his painting, it is the grace, the flat surface, the use of repetition, the perfection of form. It is his genius for clarity of shape, for purity of line along with his varied subject matter (the funnies, old photographs, the First World War) that distinguish him.

In Ulm where we went after documenta 5 opened in the summer of 1972, Jack saw his first Gothic cathedral, and as we sat later in a cafe by one of the little canals there, reading the book on the Ulmer Munster, Jack said, “My painting like the German Gothic style aims at thin construction and precise clean shaping.” “I just like the idea,” he added because he makes it a rule not to talk about his work and above all not to catch himself sounding eloquent. Seeing this now he is shocked. “I call that hubris,” Jack says. “Comparing myself to a cathedral. Are you sure I said that? It’s a sin.” I know he said it because it caught my fancy and I wrote it down in my notebook, but he wasn’t comparing himself to the cathedral, he just thought the phrase in the guidebook applied to his work.

At documenta in Kassel (that lovely city high on the hill looking out over the green valley of River Fulda where once upon a time the king of Hessen made his Hessians play at war games on the water) Dan Graham said one morning at breakfast that Jack because he falls into no category, had very nearly baffled the German curator planners of documenta with their German necessity for logic. He had very nearly baffled them, but not quite, for with the most subtle design on their part Jack was given a room of his own at the back of the Neue Galerie, at the back, neatly separating two galleries devoted to Neuer Realismus, directly downstairs from the category of lndividuelle Mythologien; and as you come upstairs from the gallery devoted to Politische Propaganda and enter Jack’s room you encounter his painting, “Chinese!”

Jack feels a kinship with Douanier Rousseau. “You are both primitives,” I say, fumbling. “No,” Jack says with authority: “We are both surrealists.”

I think (afterthought) that in Jack’s work, as in Rousseau’s, the charm of the primitive is combined with the elegance of the classic.

Some people liken Jack to Picabia, but Jack doesn’t see that. Some liken him to Klimt. He doesn’t see that exactly, but in another way he does. “He was self-taught like me,” Jack says.

“What do you mean amateur!” Tillie Olsen says in her studio at MacDowell where we have gone for Christmas.

“He didn’t really know what he was doing,” Jack says. “He was a physician, I think. He just kept on painting until he got it right.”

“I’m not a real painter,” Jack says. “I’m getting away with murder. I don’t really know-how. I can only do what I do.”

“Ah,” says Tillie, delighted. “What Florence Howe calls the working class fear of being found out. You never think you really know if you learned it by yourself if you’re the first generation. You always feel you are covering up.”

Another time Jack said, “I’m not a real painter. The real painters went to Yale and studied with Albers.” Also, he thinks it’s because of his lack of education, his lack of training that he is as he is, that is to say, original. His talent is in part defined by his limitations, by the lack of certain skills. If he could paint whatever he wanted, he wouldn’t be John Wesley.

The day before Christmas M calls and Jack spends about an hour in the phone booth at MacDowell while M reads him what he has written. Jack is madly delighted. He loves every word of it. Later he tells me he told M, “By the time you are thirty the whole world will be in love with you.” We both believe this to be a fact.

Since we arrived at MacDowell Jack has been working like one possessed. The first morning he bought paint and painted the wall of the Cheney Studio which had been allowed to deteriorate miserably. He painted the walls white (as they had been once) and since then his small paintings on paper and the larger canvases have one after another, day by day, filled with color. In the evenings I find them lined up along the wall. The empty rooms of Bumstead’s house. His chair. His slippers by the bed. His bathtub filled with water. And no one is there. The bottom of the stairs, the empty hall, the orange banister. And no one is home. The colors are bright, pure; the lines are pure; there is a kind of perfect harmony, and there is light. The paintings are as luminous as scenes of childhood memory. The empty rooms are haunting; there is a presence there. Life. The rooms are haunting and yet, at the same time, sensually so lovely. These are beautiful paintings.

Something new has happened in Jack, in his work; it is as if he has broken through in his work into a new state of consciousness. He is very high strung, keyed up. He can’t sleep. He wakes dreaming of colors. He goes to breakfast early, then to his studio.

“Blessed state,” Tillie says when I tell her because I am partly worried about him (while also I am very excited, almost euphoric thinking of what he is painting).

These paintings are very personal to Jack, more personal than anything he has ever painted before, he tells me. “It’s really my house when I was little, ” he says. “Those lamps, those curtains, that chair. They were in my house then,” he says. “It’s really my father I am looking for,” he says another time. “My father was like Bumstead. He was thin like Bumstead and he wore a tie to work, and when he came home from work in the evening he tipped his hat to the neighbors.”

“I’m seeking Ner Wesley,” Jack said. Ner was the name of Jack’s father as well as the name of his son.

In the painting, he is seeking Ner Wesley, his father, who died of a stroke in the bathroom at 12 o’clock noon one Saturday when he was 38, and Jack was five. His father had gone to work that morning and come home a little early because he wasn’t feeling well.

Jack saw him lying out in the bathroom, and after that, his father was gone. And after that, a few years after, Jack went to live in the orphanage, the McKinley Home for Boys and stayed there until his mother married again.

Sunday, December 30, just before Jack will have to move his studio, I bring Tillie to see Jack’s paintings. We walk across the snowy fields, through the snowy woods, under the tall old pines (hallowed place) where we see Monadnock; and then we walk down over the brow of the hill a bit to the Cheney behind the stone wall. Inside we stand a long time looking at the paintings, not talking. Tillie goes from one to the next. I feel how strongly she feels them, how moved she is. I feel her reverence, and my blood rises to my throat. I am close to tears. The light. The light. In here the light in the paintings is somehow more concentrated, more luminous than the light on the snow outside.

“Jack sees how mortal we are, how perishable,” Tillie says. “He sees how our things outlast us. Those slippers. That chair. That lamp.”

She stands before the green empty corner of a room with a window. (“B’s Window,” Jack calls it later.)

“What is it?” she says. “That corner with the window. The emptiness. What is it that makes it so perfect?”

What is it? I don’t know either. The Tao, the breath of life, the being in the painting. How is it that it is there in some and in others perhaps not quite? It is the thing some artists may never capture, no matter how skilled they are. This is the thing they may never capture, not in a whole lifetime. It is the miracle of life. The Chinese can analyze it.

For us it is mysterious. Somehow it has happened here that the lines just as they are, the colors, the space of the floor, the rug with its wrinkles, the window just there with its view of green trees, the curtains; somehow it has happened that all these have gone together to bring to life a sense of absence which is presence. Life is here.

“The technique is so different,” Tillie says. “And yet it has the feel of certain of Munch’s paintings. It has the feeling of that room of Hopper’s.”

In the studio on that snow full sunlit day, Tillie spends a long time looking carefully at the orange banister at the bottom of the stairs. “Look,” she says. “Look at the lines. How they vary. The irregularities.” She is tracing in air, close, the lines of the banisters.

At dinner one evening when Jack isn’t there someone asks about Jack’s work. “He’s a Pop painter, isn’t he?”

“No,” says Tillie firmly. “Jack is not a Pop painter. He is a painter of mortality.”

January 1974. We are back in New York. Jack’s show will open at Robert Elkon’s on February 9. M is rewriting the article about Jack. He is rewriting. At first, we lose heart, but then his spirit revives us. It’s getting better and better, he says. He’s very excited about it.

While we’ve been in New Hampshire he’s been all over the city talking to people, interviewing them, mastering new concepts, learning the language of art criticism.

M is thinking about Jack and animals. Jack and animals. Jack and animal symbolism. He is thinking about “Cheep” painted in 1962, the first of the animal paintings—baby birds in a nest with their beaks wide open, and above them the parent birds hover, each with a worm. “Hunger,” says Michael quizzically. “Hunger.” And bears.

He’s thinking of a pointing called “Honey Pot.” “Bears like honey,” M says, smiling mysteriously. “Hmmm.” He is thinking in particular about the polar bear embracing the sleeping woman in the painting called “Turkey.” Above the bear stand three pink turkeys. “What do the turkeys mean,” asks M.

“Turkeys are the dumbest animal there is,” says Jack. “They are so dumb, domestic turkeys, that if it starts to rain they look up in curiosity, and the rain will fill their lungs and drown them. You can’t leave turkeys out in the rain.”

M wants to go to the zoo with Jack. He says Douanier Rousseau spent all his time in the zoo in Paris and that’s where he painted his jungle scenes. Jack says Rousseau got his animals from a child’s book of animal illustrations.

M is right about Jack and animals. Jack is kind and very warm (literally, physically his skin is warm, even hot sometimes). He identifies with animals and they feel his sympathy. (Busy dogs hurrying along the street on some important business are distracted from it if Jack passes; they stop to investigate Jack and go beside themselves with joy.) When we went to Central Park Zoo the lion roared for us. He roared and roared; his stomach puffed in and out and his veins stood out; he roared until finally the keeper came and patted his nose and the lion melted, rubbed his mane against the edge of the cage to be petted some more. For weeks after that from time to time Jack imagined he was that lion. He roared—even in the streets at night.

February 7. The paintings go off to the gallery to be hung. Jack and I have to drive out to Greenburg, New York for me to give a reading in the library there.

Late at night on the way home, we drive down Madison Avenue and stop to look at “B’s Hats” in the window up there on the second floor, up there on Madison Avenue where no one passes on foot this time of night. Up there in the lighted window, the hats float silently over the green lawn; silently they float at night with no one but us to see them, and silently joyously they will float through the day in the midst of the noise of New York, and they’ll float on just that way whether anyone looks up to see them or not.

February 9, the day of the Opening, Tillie, who cannot come down for the occasion, writes, “‘Absence is condensed presence,’ Emily Dickinson wrote and you, Jack, paint. The chair is empty, as the shoes, and the clothes bodiless in the closet, and the hats fly in the wind, and yet everywhere the condensed presence.” And Tillie quotes the lines from Rilke that “Searching for Bumstead” made her think of: “all this that’s here so fleeting/ seems to require us and strangely concern us/us, the most fleeting of all.”