Robert Irwin, Whitney Museum of American Art

In 2015 the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York will move from its current location on Madison Avenue to a new building on Gansevoort Street. In light of this move, the museum took the opportunity this past summer to re-install Robert Irwin’s 1977 Scrim veil—Black rectangle—Natural light, Whitney Museum of American Art, a work expressly conceived for the fourth-floor gallery. The artist Jason Tomme documented the installation of the work and files this report.

“People looked into the room, didn’t see anything and walked right back out”: This is the way Robert Irwin described some visitors’ reaction to the original 1977 installation of Scrim veil—Black rectangle—Natural light, Whitney Museum of American Art in Lawrence Weschler’s classic biography of the artist. Fast forward to the 2013 re-installation of Irwin’s seminal work, and once again people have the opportunity to look into the room and decide if they see anything or not. For those of us who don’t walk right back out, but stay in the room, what might we actually be seeing? Does the “experience” that both artist and museum hoped would be compelling in the ‘70s still compel now? This being the first time a site-specific installation of Irwin’s has been reinstalled, I was curious about many things, including how the experience of this work might be affected by a sense of its own history.

I had the opportunity to visit the Whitney’s fourth-floor gallery during the installation of Black rectangle, to observe and take some photos for the purpose of this article. I’m also a fan and admirer of Irwin’s work. What immediately struck me during the hustle of installers preparing the space was a sense of tension (maybe just my own). What would this all add up to, exactly? This particular tension might be different from what I imagine Irwin faced upon Black rectangle’s maiden voyage, which is to say: will it work? The question is as heady as it is mundane. Irwin, for example, recalls a consulting engineer being convinced that the scrim material would simply not hold. It held. And the installation did work, by all accounts. Despite this question having been resolved thirty-six years ago, a new generation of curators and installers faced a kindred tension: will it work the same?

The Whitney Museum owns the original piece, but in the same way an institution owns any ephemeral work that doesn’t rely on original materials to be re-staged. So no, there isn’t a crate with Irwin’s original scrim and black paint kept in storage. What the museum does have is the rights to the work (to only be installed in this exact location) and installation documents. And since Irwin himself was not present during the physical reinstallation, those documents, along with Irwin’s instructions and the curators’ coordination—not to mention the know-how of seasoned installers—is how things got done. But of course no one in this equation had seen the original work nor knew what this piece would do, exactly. (If you weren’t counting Irwin, of course.)

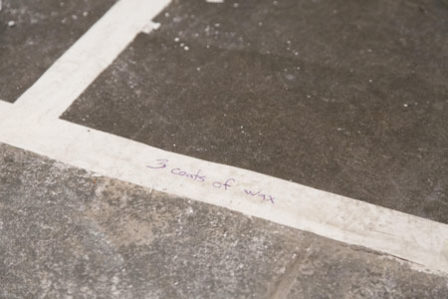

Irwin, by all accounts, was interested in restoring the original conditions of the room that existed in 1977—perhaps not a monumental task, since the gallery hasn’t structurally changed from Marcel Breuer’s original design, of which every single feature, floor to ceiling, was calculated into Irwin’s original artwork. Some things had changed however. Namely, the floor itself, labeled by Irwin as the “the Floor Plane,” was not as dark as he recalled. To remedy this, the curators arranged for the floor to be waxed, restoring a glossy darker value to the stone, which had taken on a lighter, dustier, more matte finish. This was restoration for a good reason, because upon completion, it’s revealed to be critical that Irwin’s black rectangle repeats and echoes itself within the room, and beyond…

A brief description of the piece: first imagine the large Whitney gallery (117 ft x ?) open and unobstructed. Then one of Irwin’s signature scrims, the “scrim veil” (117 ft x 11 ½ ft) is suspended from the ceiling and bisects the gallery longitudinally. The suspended scrim doesn’t drop to the floor. It stops at more or less eye level of a 6’2” male artist known for wearing a baseball hat and drinking Cokes. This hanging scrim is anchored and made taught by a black aluminum rectangular bar that runs the length of the scrim and is three inches tall. And last, the room has a single black painted line, also three inches tall, that runs the perimeter of the entire room at precisely the same height as the black bar capping the scrim. One thing that comes into focus here in quite a literal way, in case you missed it in Irwin’s title, is this notion of the rectangle, linearity, and notions of enclosure. The rectangle itself, for example, is a thing to be examined as a physical presence, and perhaps an idea, along with, unmistakably, our bodies’ relationship to it. So the darkened floor—that thing we’re walking on as we gaze around—is not at all peripheral to this. It is more than “ground.”

Although it’s a familiar by-line to Irwin, it is still helpful to reference “Light and Space” here, the movement to which Irwin is historically connected. For my money it’s the best title ever created for an art movement. It’s like if you were a chef and trying to invent a new culinary trend and called it the “food and taste” school. Yes, exactly! Just go for the essence of things, make really excellent, tasty food, while perhaps bending a few rules (and honoring others), and see what happens. If you give your school this wonderful name, it really must deliver, right? The Light and Space movement set its sights in a similar fashion, I think. It aimed to take two of the broadest, most present and common (but potentially complex) things in our day-to-day experience—namely, space, light, and physical matter—and confound or enhance our relationship to them. Irwin’s particular brand of seemingly “reductive” material use invites us to be newly aware of the function and potential of both material and the things around it. Or in other words, the goal is to highlight our sense of “perception”—the word Irwin relies upon much more insightfully than either “light” or “space” to describe his pursuits.

But light as a substance is of course critical here. In the gallery there is no electrical lighting. The room is stripped of fixtures and bulbs, leaving the concrete grid of the ceiling unobstructed and revealed. Without electricity, the room is almost exclusively lit by Marcel Breuer’s large iconic trapezoidal window. (The auxiliary gallery, separately lit, is also accessible from this room via a small entry.) And here the artist has removed the tinted film that normally covers the glass to both allow more light in and allow the outside city to be more visible and present (the film being something we might not have even known was present before, if indeed we realize it has been removed). As you might imagine, as the light changes, so does the room. Everything indoors slowly transforms as the day moves. This affects the color, the perceived weight of the scrim, and the overall atmosphere. In other words, the changing of the day affects the sense of presence of the room. But it also has a strong relationship to your sense of the human body, both your own and other people’s. The numerous silhouetted or shadowy bodies drifting through the space offers its own lo-fi spectacle. (As for yourself, if you’re taller than 5’6”, the perfect way to get bodily affirmation is to misgauge the height of the suspended bar, accidentally knock it with your head, and watch it reverberate down the scrim. You do exist after all.)

The aforementioned removal of the tinted film from the window gives us a clue to how Irwin is thinking about this work. He wants us to participate in the artwork and be absorbed by it. But we can’t stay there forever. So like any good Newtonian reaction, this absorptive energy doesn’t stay put and must reflect outward. By Irwin’s calculations, into the city it goes—the ultimate grid, home to some pretty serious lines and rectangles.

The totality of the original 1977 work indeed expanded on this idea even more, as Irwin had also staged corresponding works throughout the city, titled “New York Projections.” These works further played with rectangle and line, along with our perceptions and awareness of them in our environment. They included “Black Plane,” a large black painted square that covered the entire asphalt intersection of 42nd St. and 5th Avenue, and “Line rectangle,” which consisted of suspended nylon ropes running between the tops of buildings 4 and 5 of the World Trade Center. This created a nearly invisibly framed, aerial rectangle floating above the courtyard. Both works seem to push the limits of presence and challenge our perspective on how and where we are conditioned to see art. I would’ve liked to have witnessed these; however, even without these pieces, the re-installation offers a compelling way to measure the passage of time with respect to Irwin’s gaze toward the city. Because now we are invited to measure our own perceptions of change in landscape and modern life compared to a previous version of the city, decades past. To solidify this in my mind, I began to anthropomorphize Black Rectangle into a time traveler who had jettisoned into the future where things aren’t radically different, except that things are kind of radically different.

Here I’m intrigued for a few reasons. First, the spaces of New York City. Structurally, and from a distance, 1977 New York very much resembles today’s New York. One need only walk down one flight of stairs in the Whitney and view the concurrent Edward Hopper drawing show to be reminded of the enduring presence of pre-war architecture that continues to anchor our urban existence here in the city decade upon decade. But of course much has indeed changed. Of the dozen tallest buildings in Manhattan, half have been built since 1977. And of course one could argue that 9/11 delivered us the most horror-sublime (in the Burkean sense, which is separate from beauty—more like the exhilarated processing of terror) interaction with architecture ever—two of the most iconic rectangles to ever dot the earth vanishing before our eyes (which resulted in two mournful public artworks, both evoking the yin yang of presence and absence: the annually staged “Tribute in Light” and the permanent “9/11 Memorial.” I wonder how Irwin views these works?).

Entire communities have relocated too since then. Like the artists and galleries of Soho. The galleries of course shifted to Chelsea, recently spawning a newly gilded architectural playground of condos, offices, and hotels, not to mention the future home of the Whitney. While the artists shifted to, well, Bushwick.

Additionally, if the notion is true that the pace of a wired, technological life is always speeding up, then how do Irwin’s rectangles and lines hold their own against thirty-five years of constant acceleration? The compact black rectangle that is the iPhone is an especially loaded marker for change here, where on one occasion I noticed multiple blooms of rectangular screen-light drifting through the picture-taking crowd, noticeably affecting the room’s aesthetic and feel (it wasn’t bad). Not to mention the very likely scenario where a snapshot of the room is posted or “shared” in the very moment of experiencing the room. This undoubtedly exerts an effect somewhere along this chain of real time “experiencing,” whether it be for the sharer, the share-y, or me standing next to this transaction. Or all of the above. So again, more broadly speaking—how does this time traveler, which was once (and still is?) at the leading edge of a certain type of aesthetic and perceptual inquiry, fare amongst such dynamic change?

If you’re still in the gallery, floating around, still looking, this is probably an easy question to answer. However, maybe that’s not the only question we should be asking. Maybe when we encounter a time traveler, we should also ask how we hold up to it, along with the values that spawned it. How do the values from a previous “spirit of the age” rank now? And what does that say about our own age’s “spirit”? (It’s often easy to overlook the role of this “spirit of the age” when it comes to Irwin’s own early breakthroughs, due to the very much earned strength and charm of his biography).

I found myself lingering on some of these questions long enough to be convinced that the time traveling aspect of this work, however it translates, does indeed add value to our experience with it. Even if it mystifies. And just like the images of Hopper’s New York, it is something that has endured and still maintains presence. This presence is a physical, real-world presence—a high-quality artwork. And also a historical presence—a significant thing to be revisited, studied, and experienced—with or without a fixed sense of memory.

Perhaps that last notion, of something being “fixed” or not, relates to something Irwin wrote in the original 1977 catalogue to this exhibition:

Now, if one day you should be visited by a doubt or a simple curiosity that everything there is to know, is known, or is imminently available…being already committed to those values held at the center of the milieu, it may strike you that this is the least likely place to ask real questions for justifications of those views. All the more reason that we should begin by examining, one at a time, the character of those commitments, values, methods, and places we have been given to hold so dear.

While spending time photographing the install, I was reminded of Irwin’s optimism. I’ve always viewed him and his projects in this light. It’s impossible to read the Weschler book and not walk away with an impression of optimism, or when you hear Irwin speak, or indeed, in viewing the work itself. Maybe it’s a California sunshine thing, or a product of Irwin’s proud happy childhood (as he jokingly describes it—a thing New Yorkers hate to hear about), but it doesn’t really matter. That optimism for me translates into the ability of a work of art to promote multitudes of encounters—unpredictable encounters. The conditions of the work are measured, precise, and considered, but the outcomes and expectations of experience can be pretty wide open. This openness strikes me as a form of optimism toward discovery and beauty. Maybe more, but that’s already a lot. In any case, it’s a philosophy laid bare, I think. So I view the photographs in a similar way, where the conditions of this particular event, and the openness of it, create opportunities for something possibly unique, illuminating a process that may be both mysterious and familiar at once.